“You should call a mediator,” my friend the mediator suggests.

“I thought they’re just for marriages that want to stay out of court,” I say, picking at the top of a muffin, hiding behind sunglasses.

“They are mostly, but some work with families too. Particularly in situations like the one you’re in with your sister.”

The “situation” with my sister is one of the reasons I rarely leave the house without Jackie-O sunglasses. I never know when I’m going to be blinded by tears and I’m tired of people looking at my sad, puffy eyes. Four years ago, my mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. From what I know now, the way it was first detected is pretty common.

Mom was no longer able to fill out bank slips, she was fighting with waiters over check amounts, and repeating herself, sometimes every three sentences. I live in Los Angeles, 3,000 miles away from her, and didn’t see her enough to spot a problem. It was her friend Minnie, Mom’s Lincoln Center theater date, who noticed and called me right away.

“Something is wrong,” Minnie said, in the characteristically unsympathetic and direct way that I find most New York City women over 75 speak. She was calling from what sounded like the street outside Fairway market on 74th and Broadway, two blocks from where my mother lives.

I thanked her, hung up, and called my only sister. After college, my sister had settled in Boston and still lived there with her husband and two high-school age children. Both of us were surprised to hear that our hard charging mother’s competence, especially around money, was slipping. We agreed to meet at her apartment ASAP.

My sister arrived first. “It’s pretty bad,” she told me as I waited at LAX to board my flight. Newspapers and bills were piled everywhere, dog hair covered the surfaces like snow, dog pee stained the rugs.

My very anxious mother kept screaming at her, “Why are you here? Everything’s fine!”

My arrival the next day didn’t make Mom feel any better. The three of us hadn’t been in a room together in years—she knew the jig was up. Like many with Alzheimer’s, she’d been covering it up for quite a while. I thought back to her most recent visit to L.A., I had taken her with my sons to Home Depot and then not been able to find her. She had wandered out to the parking lot, thinking we had left her.

“Why would you do that?” I asked, worried—and so mad at her.

I wondered that a lot in the beginning. Why would a woman who lived alone for over 15 years and worked in upper-level management have to be reminded of the same thing 14 times?

Why would she ask me to do something for her. Then a day later, snap at me, “Why would you ever think I’d want you to do that?” in a tone clearly communicating I was at fault—and suddenly stupid. Looking back, I realized there had been a distinct period filled with a lot of “Why would you…?!” questions. Finally, we had some answers.

Despite Mom’s resistance to our being in her apartment, my sister and I went to work. We hired a caregiver recommended by the daughter of my mother’s friend, who was further along with the illness, and very dialed into local home health-care workers. We found a dog walker to (hopefully) stop her pug Buster from peeing all over the apartment because she had forgotten to take him out. Then we started looking at my mother’s finances, something she had always hidden from us.

My sister put in a call to our mother’s money manager, which is where the tension between us surfaced.

Covering the phone, she glared at me. “He says he can only talk to you about her money,” she said through clenched teeth.

“Oh.” I was as surprised as she was.

Unbeknownst to either of us, my mother had decided that my sister, given her expertise, would handle the health-care decisions. And me, given my—I dunno, lack of any expertise, I would be in charge of paying her bills. If Mom had talked to us about this ahead of time, she could have spared us the painful surprise of that moment. But Mom had never been interested in conversations about her future.

When dealing with a parent who has Alzheimer’s, you’re often forced to make decisions in the moment that trigger a whole lifetime of memories. We do not make these choices for our loved ones in isolation from our past.

This was one of the toughest aspects of figuring out her care. My sister had a history of feeling overtaken, overshadowed, and outdone by me. I had a history of feeling hated by her—and burying my feelings so I wouldn’t make things worse. And there we were, after living apart for 20 years, playing out this dynamic all over again.

But we had no time to address any of that, we had a job to do—hire caregivers to keep our mother safe. To our credit, we did. Then we returned to our respective homes on opposite sides of the country.

Two weeks later, our mother fired everyone.

First to go, the Geriatric Care Manager we had found to oversee our mother’s care from ground zero. My mother hated her on sight. Her calm, helpful presence just confirmed Mom’s suspicion that she was losing her mind. In the early stages after we had learned it was Alzheimer’s, our mother was surprisingly aware that she was losing her grip on the world. “More than any patient I’ve ever had before,” her social worker told me.

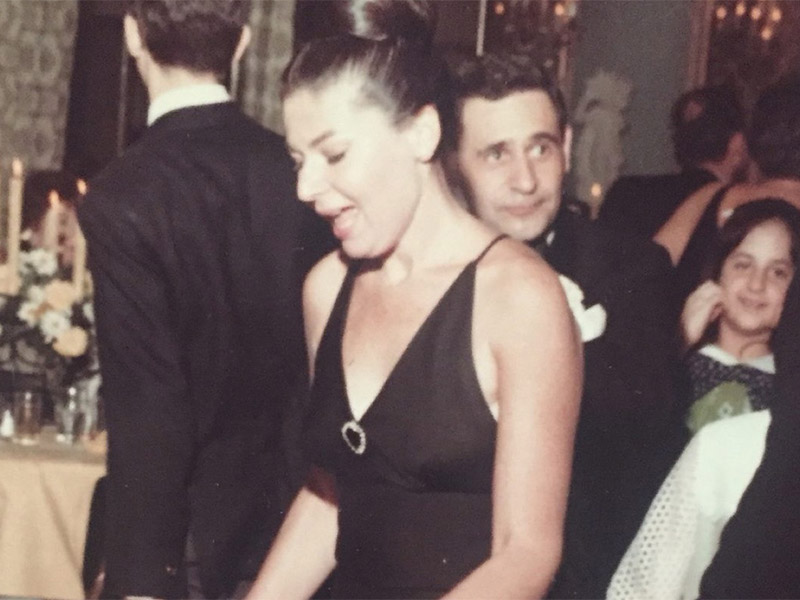

Excuse the bad grammar, but our mother was a woman who was never not in control. Her makeup was immaculate, she dressed impeccably, managed huge high-rise buildings and was savvy enough to work for Trump for a year and get paid most of what he promised her.

This was the point when communication between my sister and me started to break down. We had to hire a staff of people to cover 24-hour care. In order to qualify for my mother’s long-term health insurance—which fortunately she had, all the caregivers had to be registered with an agency.

Forms had to be filled out, checks had to be cut. Because I was the one with direct access to my mother’s savings, and the reflex to “get things done,” (what some people, particularly my sister, call “taking over”) many of our calls ended with one of us slamming down the phone. Or whatever the cell phone equivalent is. Eventually, one of us would call the other, and we’d get on with the next task.

For a fairly long time, our mother was able to live at home with round-the-clock care. My sister and I tried to carry on with our lives and our own families, without too much worry or too many emergency flights to New York.

Several years later, however, we faced our biggest challenge. New York City had become prohibitively expensive, especially adding 24-hour Alzheimer’s care to other living costs. We had to decide where to move our mother, where she would live out the rest of her life. With my sister in Boston, and me in LA, the choice was not easy.

There were practical matters of getting her to either place safely, but there was the additional and very loaded issue of which daughter she should be close to. It often felt like we were competing for the supporting role of most-beloved daughter, the one who would see Mom through her dying days. Except there was no location, no director to have the final word, and most chillingly, this was not a movie, it was our life.

Reaching a decision was not going well. We would start to talk about it, quickly our emotions would get the better of us, and again the phone would be clicked off. That’s exactly what had happened right before I met my mediator friend for coffee. The one who told me to call her colleague, Kim Deck, an LA–based mediator.

Never one to hesitate to alleviate my pain, I called Deck from my car.

“Mediation is untapped conflict dispute resolution,” she explained. Not exactly the warm and fuzzy opiate I had hoped for. But what she said next hooked me.

“For intimate relationships, marriages, siblings, you need to get underneath the law, to the feelings. Dynamic is rooted in feelings,” she explained. “If you only approach your conflict by solving the top-line issues, you miss the relationship, the thing that matters most. Ultimately, no matter where the ailing parent lives, siblings are going to be with each other.”

Had I not been driving, this last line would have stopped me in my tracks. Siblings are going to be with each other. Right. Enough with the virtual slamming of phones, we’re blood. We have to work it out.

First, Deck spoke to my sister and to me separately, using a Rashomon-esque technique to better understand our “dynamic.” Then she told each of us to write down what we wanted for our mother’s future. What were deal breakers? What could we live with? Not knowing how far along the disease had progressed for my mother, she naturally asked what my mother wanted.

“To ‘go home,’ or for someone to ‘take her away,’” I answered. “Depending on when you catch her during the day.” Sadly, that’s what my mother says most of the time now.

My sister and I are still working toward a resolution. We’re making progress, using our mediation lists to help guide our decision. One thing we firmly agree on is that we don’t want our mother spending another winter in New York City with neither of us nearby.

As we talk, I try to keep in mind what the mediator said in that first phone call when I asked, “What’s the most important tool for getting through terrible tension with a sibling?” Know your goals. For me, a good outcome is my mother in a safe place. A great outcome? That and mending my relationship with my sister.

Never being one to settle for good when great is a possibility, I’m also making a conscious effort to do one other important thing suggested by our mediator. I listen. And I try to do it with humility. Which, in these circumstances, tends to be a little more complex than it sounds.

Working with a mediator introduced me to the phrase Modus Vivendi—which is a way of being together in conflict. I love this idea. We are faced with the challenge of caring for a loved with a history as siblings that we can’t change. But if we are diligent and committed to a positive outcome, then we can emerge from this with more understanding, more compassion, and more love for each other.